The Life Giving Sun

We all like to sit in the sun. We like its warmth upon our skin. We appreciate how it is needed to ripen our fruit and our crops. We also know its danger, it can burn, ignite wildfires, cause drought and create deserts. To the ancients its nightly disappearance, and gradual loss of power during the course of a year as it yielded to winter, were sources of mythological tales. The sun is a life-giver, life sustainer, it embodies both strength and protection. To dance widdershins (clockwise in the direction of the sun) was deemed to bring fortune and luck.

For example, in Greek mythology Helios is the sun, himself the offspring of Titans (his father Hyperion - means the High One - and his mother Theia - means wide shining light). His sisters are Eos (the dawn) and Selene (the moon). Helios was portrayed wearing a crown of sun rays and he drove the chariot of the sun across the sky everyday. His cult was most prolific in the Greek Island of Rhodes (The mighty Colossus was dedicated to his honour).

In Hellenic times, Apollo becomes associated with the sun, and the Romans named it Sol. However to the Bronze-Age Scandinavians Sòl was a female deity. Sometimes she was called Sunna and her brother was Maní, the moon. Her husband, Glenr, drove the horses of the sun across the sky - although in early myth the wagon or chariot was sometimes portrayed as a boat. Some say this 'sun-boat' myth points to an Egyptian origin, but that's not necessarily true.

|

| Helios, 4th c. BC, Ilion |

For example, in Greek mythology Helios is the sun, himself the offspring of Titans (his father Hyperion - means the High One - and his mother Theia - means wide shining light). His sisters are Eos (the dawn) and Selene (the moon). Helios was portrayed wearing a crown of sun rays and he drove the chariot of the sun across the sky everyday. His cult was most prolific in the Greek Island of Rhodes (The mighty Colossus was dedicated to his honour).

|

| Trundholm Sun chariot, dated to between 1800-1600 BC though dates are contested, others believe it to date between 1100-550 BC. |

In Hellenic times, Apollo becomes associated with the sun, and the Romans named it Sol. However to the Bronze-Age Scandinavians Sòl was a female deity. Sometimes she was called Sunna and her brother was Maní, the moon. Her husband, Glenr, drove the horses of the sun across the sky - although in early myth the wagon or chariot was sometimes portrayed as a boat. Some say this 'sun-boat' myth points to an Egyptian origin, but that's not necessarily true.

The Celts and the Sun

Surviving fragments of a Gallo-Romano calendar from Coligny, France, indicate that the moon was more relevant to the Celts (at least in terms of their time telling). The amazingly detailed calendar, itself based on earlier models, it pictured above.

We know that ancient peoples aligned many of their sacred sites with the midwinter sun, and that many henges were astrologically aligned, pointing to a deep understanding of the celestial bodies, the constellations and movements of sun and moon. Surely some of this knowledge was inherited from the times of the megalith builders.

Pomponius Mela, a geographer of the 1st c. AD, wrote that the druids “claim to know the size and shape of the earth and universe, the motion of the stars and the sky and the will of the gods…”

Caesar mentions that Apollo was amongst the gods venerated by the Gauls. Apollo was associated with solar and healing properties (of course Caesar used a Roman name to describe a foreign deity).

Deities associated with the sun can be traced in northern Italy, the eastern Alps and southern Gaul, where Bēlenos was honoured; the name said to come from root Gwel, to shine. Bēlenos' worship is reflected in names such as Belluno. In Britain and Gaul there's evidence of a god named Lug, Lugh or Lleu Llaw Gyffes which means 'the bright one with the strong arm' (he threw magical spears... sun rays?). The name of this Deity is evidenced in many place names from London to Lyon.

However many scholars, including Anne Ross and Ronald Hutton, are opposed to the idea that the Celts worshiped the sun as a god, or that there were sun cults as such. But I find it hard to believe that, given the obvious veneration of the solstices (and the respect given to the motions of the year) that the sun was never considered as a deity. Solar wheels and sun discs appear in many cultures, including those considered Celtic and Germanic.

The solar wheel was developed in the Carpathian region around 3000 B.C. and spread across Europe. It often appears on gold items, strengthening its solar association, for gold is the element of the sun. In Bronze-Age Scandinavian artwork it's drawn by horses, or borne in boats or chariots (tying in with the whole sun-boat imagery and ancient mythology regarding the rise and fall of the sun). There's even archaeological evidence that Iron Age Gauls offered solar wheel images at shrines, and also cast them into sacred pools. As a symbolic gesture this is powerful, representing the sun’s departure into the ocean (the Underworld).

There's something particularly enigmatic about some of these Alchemical and medieval images of the sun. To those versed in their layers of meaning surely the images evoked a sense of the deeper mysteries, and spiritual insights, Hermetic Alchemy professed.

For example, the sun as life-giver, or protector, offering salvation seems to me a natural instinctive symbolism. Archaeological records show that burial mounds and stone circles of the megalithic period were involved in the veneration of both sun and moon. In generalising myth into principles, the sun could be seen to reflect the active principle, while the moon the passive. Equally, the sun could be said to encompass the hero and passion. In its yearly progression from the summer solstice, through the seasons toward mid-winter, it represents re-birth. A cycle of hope, which surely the ancient pastoral and pre-pastoral peoples clung to for the basic, pressing necessity of their survival.

*curiously the sun-wheel image pre-dates the invention of the wheel - thus it may be that the sun wheel's spokes are in fact sun rays.

We know that ancient peoples aligned many of their sacred sites with the midwinter sun, and that many henges were astrologically aligned, pointing to a deep understanding of the celestial bodies, the constellations and movements of sun and moon. Surely some of this knowledge was inherited from the times of the megalith builders.

|

| Stonehenge by Alan Sorrel |

Pomponius Mela, a geographer of the 1st c. AD, wrote that the druids “claim to know the size and shape of the earth and universe, the motion of the stars and the sky and the will of the gods…”

Caesar mentions that Apollo was amongst the gods venerated by the Gauls. Apollo was associated with solar and healing properties (of course Caesar used a Roman name to describe a foreign deity).

|

| Solar Crosses from 1500 BC - pic by Radan Haenger. |

|

| Scandinavian Bronze-Age carvings - the solar boat |

The Mythic Mechanics of the Sun Disc

Many myths make reference to a solar disc being drawn through the sky, while some describe how the solar deity was born across the heavens. It's possible that images of the solar wheel derive from this idea; the solar disc, combined with the wheels of a sun chariot (see the sun chariot above).*

The solar wheel was developed in the Carpathian region around 3000 B.C. and spread across Europe. It often appears on gold items, strengthening its solar association, for gold is the element of the sun. In Bronze-Age Scandinavian artwork it's drawn by horses, or borne in boats or chariots (tying in with the whole sun-boat imagery and ancient mythology regarding the rise and fall of the sun). There's even archaeological evidence that Iron Age Gauls offered solar wheel images at shrines, and also cast them into sacred pools. As a symbolic gesture this is powerful, representing the sun’s departure into the ocean (the Underworld).

|

| Scandinavian rock carving from the Bronze-age |

Mithraic Sun Links

Another sun god worshipped across the continent during the Roman invasion was that of Mithras, who enjoyed something of a cult following (though not an especially populous one - its adherents being drawn from a select cadre of Roman society, and by the military). In many ways Mithraism shared common ideas with Christianity: born of a virgin, an ultimate sacrifice, his followers addressed each other as ‘brother’, while temples were run by a ‘pater’ (father). Unlike Christianity Mithraism was tolerant of other faiths.

|

| Mithras born from the rock. |

Mithras’ roots reach far back into antiquity; having his origins in the Middle-east, a Hellenised form of the deity was worshipped in Europe, with the spread of the Roman Empire. Like Bel and Apollo, he's more a god of light, than the sun itself. Temples to him were erected along Hadrian's Wall; like the one at Housesteads, dedicated to Sol - with whom Mithras was also associated.

There's also some speculation whether Ogmios, a Celtic deity associated with the Ogham alphabet and also a solar god, was perhaps mingled with elements of this exotic deity. There is also speculation that the 6th Century bard, Taliesin, was knowledgable in the ‘mysteries’ of Mithraism.

The Alchemical Sun

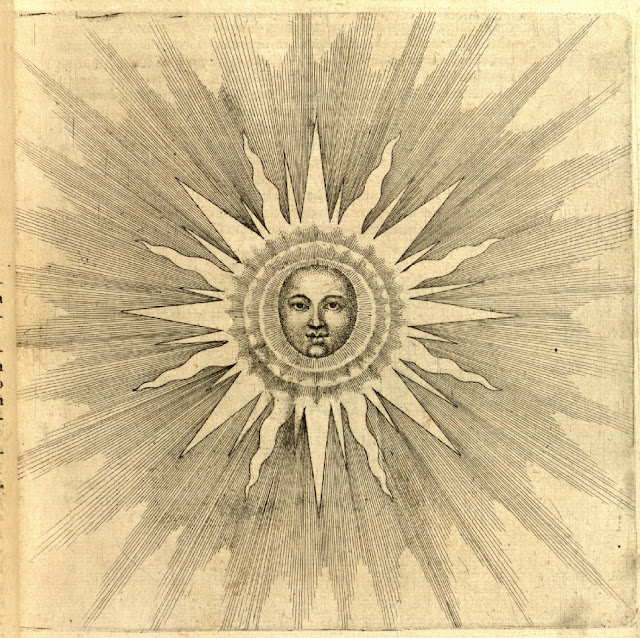

|

| Alchemical sun by Robert Fludd 17th c. AD |

In the middle-ages Alchemists viewed the sun as an active agent, as gold prepared for the work, and philosophical Sulphur. There was also Sol in homine, which was the invisible essence of celestial sun that nourished mankind's inner fires. From such aspersions, Jung, the master of symbolism and its interpretation, considered the sun as representing wholeness (especially when unified with the moon, like a king for a queen).

There's something particularly enigmatic about some of these Alchemical and medieval images of the sun. To those versed in their layers of meaning surely the images evoked a sense of the deeper mysteries, and spiritual insights, Hermetic Alchemy professed.

The Cycle of Hope

In doing the research for this piece, I’ve come to the conclusion that the sun was many things for the many different cultures, that have populated the earth throughout history. Never has there been a single unifying principle, though common themes exist between cultures.

For example, the sun as life-giver, or protector, offering salvation seems to me a natural instinctive symbolism. Archaeological records show that burial mounds and stone circles of the megalithic period were involved in the veneration of both sun and moon. In generalising myth into principles, the sun could be seen to reflect the active principle, while the moon the passive. Equally, the sun could be said to encompass the hero and passion. In its yearly progression from the summer solstice, through the seasons toward mid-winter, it represents re-birth. A cycle of hope, which surely the ancient pastoral and pre-pastoral peoples clung to for the basic, pressing necessity of their survival.

If you enjoyed this article you can Buy Me A Coffee here. Cheers.

|

| Sun horse from Balken - |

*curiously the sun-wheel image pre-dates the invention of the wheel - thus it may be that the sun wheel's spokes are in fact sun rays.

Reference

No comments:

Post a Comment