|

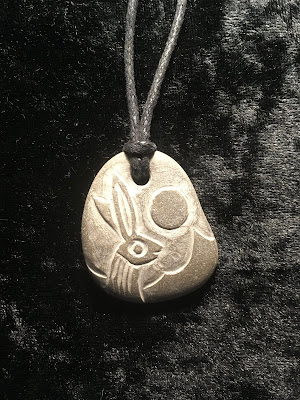

| Hand Carved Hare by Dave Migman of Stone Mad Crafts |

The Names of the Hare in English*

Dew-beater, dew-hopper,

The sitter, the grass-hopper,

Fiddlefoot, form-sitter,

Lightfoot, fern-sitter,

Stag of the cabbages, herb cropper,

Ground creeper, sitter-still,

Pintail, turn-to-hills,

Get-up-quick,

Make-fright,

White womb,

Layer with the lambs

Hare Today…

The hare is everywhere in art these days. However as their habitats are urbanised and become more inhospitable, they are less visible in their natural environment. Perhaps the popularity of “hare fayre” today speaks to the wildness within us, buried beneath a veneer of societal norms and plastic detritus.

The hare’s contradictory nature is evidenced by their ubiquity in folklore. They feature worldwide in stories of the moon and fantasy and were also anthropomorphised into everyday folks. They are comfortable in the company of rude mechanicals and divinity alike. Often confused with rabbits, their gentler cousins, we are drawn to their beauty and grace which can seem otherworldly and has inspired many legends.

The Nature of the Hare

Why then are there so many legends across the world surrounding hares? They are indigenous to every continent excluding Antarctica, yet they remain stubbornly unfamiliar. They are solitary in nature, and even leverets born in the same litter are separated at birth. Yet they are known to congregate on mountainsides and even airfields in vast numbers… and nobody knows why.

In researching this post, I encountered so much contradictory information. So little is known about their habits. In fact it was only in recent years that it was discovered that “boxing hares” are not males competing for mating rites, but females rejecting potential mates. They are rarely visible out-with springtime, when they can be seen trying to outrun cars on country roads or sitting sentinel in fields.

Hares differ from rabbits in several key ways – a hare has no home to retreat to, resting in forms above ground which makes them entirely reliant on hiding and running for survival. Their massive hearts power these high speeds. This is why they make lists of fastest animals on the planet with top speeds of up to 60km per hour. They are small prey animals with a reputation for being feisty.

Beast of Venery

As prey animals, hares have long enjoyed an elevated status and a reputation for scrappiness. In Medieval Britain, the hare was designated one of four “Beasts of Venery”. Hares were for the landed gentry only, not for peasants and poachers. Laws were passed to forbid the common man from poaching hares, as they were revered alongside the deer, boar and wolf. The unlawfulness of eating hare may have been adopted by conquerors from Celtic customs. Perhaps this status as food fit for a king only is in part responsible for the anthropomorphic interpretation of the hare as arrogant.

Whether full of bluster, like Aesop’s Hare and the housemate of Alison Uttley’s Little Grey Rabbit, or full of cunning like Brer Rabbit, hares are culturally elevated to a higher status. It is possible to see a correlation between this and their aloof, solitary nature.

Celtic and Anglo Saxon Tradition

Hares have been revered across many cultures in mythology. Both the Anglo-Saxons and Celts treated the hare as forbidden flesh excepting a ritual hunt (Celts at Beltane, Anglo Saxons at ‘Easter’ time)**. Celts viewed hares as creatures of divination. There is a well-known story of Boudicca releasing a hare as a portent during a speech. It is said that hares can shape shift, or that women (often, defined as witches) could change into hares. The Celtic warrior Oisin chased a hare and found a beautiful woman with identical injuries. There are stories too of witches, under the guise of hares, stealing milk from cows in the field.

‘I shall go into a hare,

With sorrow and sych and meickle care;And I shall go in the Devil’s name,Ay while I come home again.’

1662, Isobel Gowdie’s confession.

Moon gazing hares

The most common image by far we see of hares in art is that of the moon-gazer. The hare’s association with the moon spans across many cultures and seems to derive, in part, from their nocturnal habits and tendency to stillness. However it could also be attributable to the shape of a hare perceived in a full moon.

To Be or Not To Be…

The ancient Greeks used hares to represent both homosexual and heterosexual love. Gender fluidity is attributed to the hare in legend and they are associated with fertility in many different legends. They are associated with the god Eros and the goddess Aphrodite. It may be this reputation, along with their speed and dynamism, which led to them being used as a symbol of regeneration as well as a messenger of the gods. In Egyptian hieroglyphics, hares were most commonly used to mean ‘to be’.

The individual hare representing existence flows nicely into some of the theories about the triskele of hares. Three hares appear in a circle formation, sharing ears so that between the three ears they each have a pair. Three as a number represents community (where individuality and duality precede it). It is often associated with worship – trinities of gods or triskele patterns form a triangle of dependence and interconnectedness. A circular image appearing along the silk path, from the Far East to the south of England, is known as the “Tinner’s rabbits”. It appears carved in Romanesque churches and painted in Buddhist caves.

If you enjoyed this article you can Buy Me A Coffee here. Cheers.

Reference

The Private Life of the Hare by John Lewis-Stempel ISBN 9781473542501

The Way of the Hare by Marianne Taylor ISBN 9781472942265

The Leaping Hare by George Ewart Evans and David Thomson ISBN 9780571336050

Foot notes:

*Middle English poem, circa 13th Century, first published by ASC Ross in Proceedings of Leeds Philosophical Society, Literary and Historical Section, in 1935 (p347-77)

Translation into modern English is largely my own, Seamus Heaney has his own sweary and inaccurately translated version if you like that kind of thing!

**Easter is often referred to as having had its origins in the celebrations of the Germanic goddess ‘Oestre’ who had a hare for a companion – in reality we know very little about the extent of worship to Oestre before being referenced by Bede in 725ad and theoretically, there may well have been a host of goddesses of the spring and fertility, localised, who all became generic and celebrated under one banner… however we can readily recognise the hare’s symbolism of fertility and spring from their habits.

***oral traditions in Africa seem to make it hard to pin down an origin for this story, but there is a tradition generally of smaller, prey animals being tricksters who outwit larger creatures. There is another typical type of pan African tale which explains the origins of different animals – both aspects are present in this particular story.